|

|

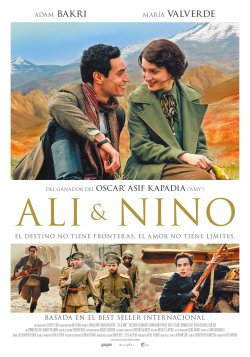

SINOPSIS

Ali, musulmán, pertenece a una familia de clase alta que mantiene un férreo poder en la ciudad. Nino es la amante de Ali, de una localidad vecina y cristiano. Ambos están tan enamorados que deciden escaparse. A partir de ahí asistiremos a la vida en común de ambos con la Primera Guerra Mundial como telón de fondo...

INTÉRPRETES

ADAM BAKRI, MARÍA VALVERDE, MANDY PATINKIN, CONNIE NIELSEN, HOMAYOUN ERSHADI, HALIT ERGENÇ, FAKHRADDIN MANAFOV, NIGAR GULAHMADOVA, PARVIZ GURBANOV, NUMAN ACAR, DANIZ TACCADIN, MEKHRIBAN ZEKI

MÁS INFORMACIÓN DE INTERÉS

![]() CÓMO SE HIZO

CÓMO SE HIZO

![]() VIDEO ENTREVISTAS

VIDEO ENTREVISTAS

![]() PREMIERE

PREMIERE

GALERÍA DE FOTOS

GALERÍA DE FOTOS

https://cineymax.es/estrenos/fichas/100-a/104233-ali-and-nino-2016#sigProId93a3e3dd40

INFORMACIÓN EXCLUSIVA

INFORMACIÓN EXCLUSIVA

BEGINNINGS IN BAKU...

An epic love story between a Muslim boy and a Christian girl, Ali and Nino is considered to be the great work of Twentieth Century literature from its native Azerbaijan. Since its initial publication in 1937, this tale of two star-crossed lovers, set to the backdrop of the First World War and the Bolshevik Revolution, has been translated into 33 languages, and reprinted nearly 100 times. That the book’s writer is still a mystery only adds to its aura; attributed to Kurban Said, a pseudonym, the authorship of Ali and Nino is debated to this day.

For producer Kris Thykier, it was the perfect source for a film. “When I first came across the book, I was looking for something that was epic, emotional and romantic,” he says. “It was a world that I’d never seen shown on film before. I loved this idea of East and West, Asian and European and Muslim and Christian; it has all these big themes tied up in a very romantic love story. It’s not only playing to the genre that I was looking to make, but it feels contemporary in terms of the underlying concepts that are in it.”

Along with his producing partner, the Azeri-born Leyla Aliyeva, Thykier spent a year acquiring the rights to the novel before he recruited a screenwriter: Christopher Hampton, the Oscar-winning screenwriter of Dangerous Liaisons. “He’s not only a great adapter of great books but he’s also a fantastic dramaturge,” says Thykier. Hampton, though, was not aware of Ali and Nino. “I must say when I got a book with a note saying it’s an Azerbaijani novel of the Thirties, I thought, ‘Give us a break!’” he laughs. “But it created such a different world from anything I’d read from that period before, I got really fascinated by it.”

One of the most intriguing aspects was Baku in the 1900s – a sprawling oil-rich city that recalls a modern-day Dubai. “It was a real crossroads,” says Hampton. “All the foreign oil companies – Nobel and Rothschild and others came in to exploit the resources. At that time, it was literally producing half the world’s oil, so it was a really enormous boom. And all the buildings that are still there in the old city went up at that time, so there’s a lot art nouveau there – whatever was the latest fashion of the pre-First World War cosmopolitan architecture.”

In 2011, before Hampton began writing, he and Thykier undertook a trip to Azerbaijan, travelling from Baku to Tbilisi in Georgia. “I never like to embark on something that’s set in another country unless I’ve been there and spent a bit of time there and absorbed the atmosphere. So when I did The Quiet American, for example, I went to Vietnam. It’s just a sensible procedure in my view. You want to get a sense of that part of the world, what it’s like and if the people are closed or open – all those sorts of things.”

After their fact-finding mission, Hampton began to work on the script and Thykier started to consider appropriate directors for the project. “It was about finding someone who was willing to be emotional,” he says. “It needed to be a smart filmmaker who could work with Christopher Hampton, who could bring the best out of the screenplay and out of the drama. But I did want somebody who was able to be romantic. And that was more difficult than you think.”

Having seen the acclaimed, BAFTA-winning documentary Senna, he began to ponder director Asif Kapadia. “It’s bizarre to get to Ali and Nino via a motor-racing documentary,” he laughs, “but it was so clearly heartfelt.” It was just what Thykier wanted. He then re-watched Kapadia’s debut fictional feature, The Warrior (2001), an exotic drama set in feudal India that offered further proof that he might be the ideal filmmaker. “The thing that joins those two movies is his willingness to tackle raw emotion head on.”

When Kapadia received Hampton’s script, he was already in the midst of cutting Amy, his hugely successful documentary about singer Amy Winehouse released in 2015. Nevertheless, Ali and Nino grabbed him. “It was this mad landscape, this world that I didn’t know, these countries I knew very little about,” he comments. “There were a lot of different elements in there – the love story, the action scenes, the war movie, the romantic story. All of these different themes seem to be mixed up in a landscape I didn’t know.”

Once on board, Kapadia joined forces with Hampton and began working on revising the script. The first task, according to Hampton, was to adjust the point of view of the novel, which is narrated by Ali, with Nino very much seen through his eyes. “The very first meeting I had with Asif, he said: ‘I read the book – it ought to be called Ali!’ So we agreed that we would try and equalise the two characters.” Of course, this meant beefing up Nino’s role considerably.

Kapadia explains: “I was really interested by her character, I must say. I just thought there was something about her...she was the emotional heart of the film. He had his journey and he makes his choices and decisions. But I thought, ‘If you’re going to move the audience, you’ve got to buy her side of the story and understand who she is.’ So really that was a big part of the development – her character, her friends, her parents. What’s going on with her? The book loses her a lot of the time.”

It wasn’t the only difficulty in adapting Ali and Nino. “One of the reasons the book was hard to adapt is that a lot of the story, the dramatic story, is in the last twenty-five percent,” says Thykier. Much of the book provides historical, religious, political and social context – such as Muharram, one of the four sacred months in the Islamic calendar where Muslims fast and even self-flagellate. As fascinating as it was, Hampton took the decision to cut it out, preferring to keep the focus on Ali and Nino.

“The big issue was to make sure that you believe this love story,” says Thykier. “When Ali has to make a choice between the woman he loves and his country, those two things don’t sit easily. It’s not an easy decision, and both parts of his character need to play. In a way, you need to fall in love with her and see him through her eyes and be emotionally attached to her in order for the whole thing to make sense. So those are the two big pieces of work that needed to be done.”

CASTING ALI AND NINO...

In the spring of 2014, the script for Ali and Nino was finally reaching a point where it was ready to shoot. Kapadia, though, had already been considering who to cast. The big decision, of course, was who to play Ali and Nino. In the case of Ali, it meant finding an actor who could fit a number of criteria: believable both as a lover and a fighter, he also had to be able to speak English but feel like he comes from Azerbaijan.

Kapadia had seen Omar, Hany Abu-Assad’s 2013 film about a young Palestinian freedom fighter, starring Adam Bakri. “When I saw Adam I thought, ‘There’s someone there that fits the bill, that’s on the way up and young enough to be believable for the age group,’” he recalls. After Skyping with Bakri, he met him in New York and again in Los Angeles, where they shot an audition tape, before Bakri was officially cast.

Bakri immediately read the novel and was swept up by the story and the opportunity to engage with a country like Azerbaijan. “It’s a point of view of a place that a lot of people didn’t know about,” he says. “Even for me, when I was first approached, I really didn’t know where Azerbaijan was. Seriously. I had to do proper research especially into this whole area they call Caucasia. I had to get myself familiar with the whole region, historically, culturally and socially.”

Still, he was taken with the character of Ali – who, as Hampton puts it goes from “someone disengaged to someone who finds a cause”, maturing over the course of seven years to go from boy to man. “He’s soulful,” says Bakri. “He loves Nino. He loves literature. He loves poetry.” In particular, says Bakri, he’s very in tune with Mother Nature. “He’s a desert guy. He’s an adventurer. He likes hunting. He likes riding horses, catching snakes, climbing mountains.”

When it came to finding Nino, Kapadia got lucky. The very first actress he saw, Spanish star Maria Velverde, he eventually cast. “I saw a lot of girls,” recalls Kapadia. “There were people that might’ve been a more obvious choice, but none of them were as good as Maria, emotionally. She just had a real presence, she looked amazing, she was a really good actor and she just came in and blew me away with her casting…so having seen I don’t know how many girls, I kept going back to the first girl that I met.”

Valverde, who wasn’t aware of the book before she came on board, was bowled over at the chance to play Nino, steering her from what Hampton calls “a rather frivolous party girl” to a young woman devoted to her man. “Nino is an amazing woman, she’s very energetic and enthusiastic about life,” she says. “She an intelligent woman who’s really passionate. She really loves Ali, more than anything in the world. And she’ll do anything to be with to him.”

While finding the leads was vital, the supporting players were just as crucial. “It was a tough one to cast,” admits Kapadia, who felt he needed to replicate the cosmopolitan nature of the book, which featured characters from Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia and Russia. “It’s a weird melting pot of East and West, Asia and Europe, Persia, Iran, Georgia, Christians, Muslims, all somehow in the same place.”

With this in mind, it meant seeking out an international set of actors, rather than what Thykier calls “stunt casting” that might involve selecting more recognisable – but less credible – faces. Together with casting director Shaheen Baig, Kapadia embarked on a search that saw him select actors from all over the globe. “That can be exciting, but it can be a nightmare!” laughs Kapadia. “Because of all of the different accents and how much time you actually have with them, and whether you get to even meet them before you cast them.”

With many of the cast also working in English as a second language, the linguistic issues were as prominent as the logistical ones. But Kapadia felt it was part of the challenge, to seamlessly blend together actors from Europe, North Africa, the Middle East and America with more locally-based performers. “Individually, they’re all brilliant, from their countries,” says the director. “You’re just hoping the whole mix works.”

To play Nino’s parents, Kapadia went for experience, casting American actor Mandy Patinkin as her father Grigor Kipiani and the Danish-born Connie Nielsen as her mother Tamar. Already a big fan of Christopher Hampton’s work, Patinkin read the script and loved it. “I thought it was epic – a classical, old-fashioned love story, in a way that they just don’t make movies anymore. A period piece – a Romeo and Juliet story that could’ve been written this morning, in terms of a Christian girl and a Muslim boy as the world runs insane around them. I just thought it was beautiful.”

Working from the outside in, Patinkin started by perfecting his Russian accent. Collaborating with a voice coach, he also met some people in New York, making tapes of their voices, before he flew to Baku. He also changed his look – shaving off the beard that will be familiar to anyone that’s seen him as CIA man Saul Berenson in HBO drama Homeland and adopting a fake ’tache. “If I had my own moustache, even grown full out, it would never have looked like this,” he laughs. “Oh my God – I looked in the mirror…it wasn’t me!”

Gladiator star Nielsen, meanwhile, was thrilled at the chance of working with Kapadia. “For me, Senna was so awe-inspiring,” she states. “His heart just comes through. His ability to feel passionately about his subjects and the people that he’s covering is almost unique. He really searches for the one thing in those human beings that define why we should care about the fact that they existed. And I don’t think I can say that about many filmmakers. It’s a very rare talent.”

She was also fascinated by the period of history that Ali and Nino covers, with Europe in chaos and revolution brewing. “Here was the opportunity to participate in a film that was built on these recollections of lifestyle and the attempt to birth a nation under the pressure of these large empires that surround them. I just thought that was such an interesting thing. And we need to know more about these countries. I wanted to be part of telling these stories that help us engage with these neighbours.”

Both actors understood their characters implicitly. Kipiani “loves his daughter”, says Patinkin. “His daughter is first and foremost in his life. He is rather ruthless when it comes to business but when it comes to his daughter, she trumps all. He’s a bit of a soft touch. At the same time, he’s always trying please everyone around him, stay in power and pull the strings of the business world, in oil. That’s what he lives and breathes. That’s where he gets his power.”

As for his wife, she’s over-protective of Nino, says Nielsen. “She is really, really scared of her daughter marrying a Muslim; she’s scared that she will end up in a harem, and that she’s going to have no say in her life. That is the difference. She’s an ex-pat, a typical ex-pat, and she’s judging the country in which she lives. But she’s also a mother and a woman, and she wants her beautiful daughter to have choices that include freedom to make those choices.”

Playing Ali’s father is Iranian-born Homayoun Ershadi, whose past credits include The Kite Runner, Zero Dark Thirty and the Cannes-winning Taste of Cherry. Like most he didn’t know the book – and, unable to find a copy of it translated into his native Farsi, had to wait until he arrived in Baku to read it. But he was immediately taken with the story’s depiction of love across religions. “It’s very difficult for a Muslim when you get married to a non-Muslim,” he comments. “He or she has to change their religion to be a Muslim, but in this case, Ali’s father doesn’t push the girl to change her religion. It’s a good lesson, especially for these days.”

Rounding out the cast is a number of other actors hugely successful in their own territories. Cast as Fatali, the lawyer and family-friend who later is appointed Prime Minister as Azerbaijan seeks independence from the Russian empire, was Halit Ergenç – “a massive star in Turkey and the Middle East”, notes Thykier. Moroccan actor Assaad Bouab was recruited to play Ali’s friend Ilyas, while the Italian actor/producer Riccardo Scamarcio, who shot to fame in The Best of Youth and Romanzo Criminale, won the role of Malik.

A particularly tricky character, given he kidnaps Nino in the hope of marrying her, Scamarcio was up for the challenge. “I think at the beginning he really wants to help them, but then he falls in love with her, so – yeah – what he does in the movie is a little bit opportunistic. Particularly when he kidnaps her! But if we think that he’s in love with her, he has an opportunity to stay with her. He proposes to move to Moscow to get married. Even for her, he represents, in a way, the European way to live. He reads a lot. He goes around the world, because he’s a businessman. He’s sophisticated.”

SCOUTING, DESIGNING AND SHOOTING ALI AND NINO...

Shooting entirely on foreign soil, one of the key personnel in making Ali and Nino was always going to be locations manager Andy Eliot, who came on board eighteen months before the shoot. With no film industry to speak of in Azerbaijan, “Kris’ idea was to get someone out here to literally map the country,” says Eliot, who spent five weeks travelling the country with a local guide in a 4x4 vehicle. “They just wanted to get a photographic record of anything of any interest.”

Despite the relative small size of Azerbaijan, the country’s diverse landscape stretches from tea plantations in the south to deserts to mountainous regions. “We’ve tried to pull in as much as we can of the beauty because it is actually quite an extraordinary country,” says Eliot. “Once you get out in the city…of the fourteen micro-climates of the world, eleven of them exist in Azerbaijan.”

The locations may be spectacular but setting up a production in a country that has rarely seen a movie shoot there was another matter. While the James Bond team shot scenes in the oil fields near Baku for 1999’s The World Is Not Enough, Azerbaijan had never before played host to a major international production for almost an entire shoot. “We had enormous amounts of support,” says Thykier, “but it’s also a country where the film infrastructure hasn’t existed for twenty years since the end of the Soviet rule.”

With assistance from the Azerbaijani government and military, there was also a willingness from the locals to help out because the book, put simply, was a national treasure. “It certainly is the Romeo and Juliet of the region,” says Eliot. “Most people that you meet, certainly in the city, have read it. It’s close to their heart.” With Eliot scouting almost sixty different locations in total, it made for a logistically challenging shoot – with the production trekking across Azerbaijan and Turkey, which doubled for Tbilisi in Georgia and Tehran.

As the locations came into focus, so Thykier and Kapadia began to gather their production team. Experience counted when it came to recruiting the heads of department: Turkish-born cinematographer, Gökhan Tiryaki, famed for his work with Nuri Bilge Ceylan, including the Palme d’Or-winning Winter Sleep; production designer Carlos Conti, whose credits include Betty Blue, The Motorcycle Diaries and The Man Who Cried; and costume designer Michele Clapton, fresh from Game of Thrones.

With a production that required hundreds of extras – soldiers, musicians, market traders, businessmen and noble-folk – one of the busiest departments was wardrobe. Clapton was keen to get everything as historically accurate as possible, particularly tricky when it came to the military uniforms for the Tsarist, Azeri and Bolshevik troops. “Obviously the Bolsheviks took things from wherever they came from – so they’d be part Tsarist – and the Azeri regulars would also be part Tsarist,” she explains. “It was a real muddle at one stage.”

Using a military advisor, Clapton also met collectors of Azeri costumes, who allowed her to browse their clothing finds and even borrow some pieces, right down to the coins that adorn Nino’s hats. For Valverde, collaborating with Clapton and her team was crucial when it came to getting into character. “It wouldn’t have been the same without them,” she says. “We had to build a character that we first see as a teenager and then develops into a proper woman. Every detail was so important, the way she looked, her hair, her make-up.”

In the case of Ali, there were close to forty costume changes, as he goes from a student to a husband-in-exile to a soldier and finally a diplomat. “Most wealthy Azeris and oil barons dressed in European costume,” says Clapton, who clothed Ali in western-style outfits for the first act before switching to traditional costumes, for the scenes with Ali and Nino in the mountainous village, and more austere robes for the sequence where Ali joins a pregnant Nino in Tehran. Finally, for the moment he becomes the Deputy Prime Minister of the new Republic of Azerbaijan, he returns to a “blend” of European and Azeri influence.

Meanwhile, the art department set about recreating Baku from the early 1900s. One of the big locations to dress was Duma Square. In Ali and Nino, it’s the bustling heart of the city, filled with market stalls, wood fires, traders, military personnel and even camels. In modern-day Baku, though, the square was flush with CCTV cameras, advertising hoardings, lampposts, cars, a security booth and even a large clock. All of which had to be removed. “I would say there has been a greater transformation in this area by us than I’ve seen on any film that I’ve worked on,” says art director James Wakefield. “I’m so pleased with what we achieved.”

Patinkin was just one of the actors who was taken aback by what the production team managed when he arrived on set. “The whole place looks like you’re in another world. Between the art department and locations, they transformed you. You were in 1914-1918. And we really were in another world, another environment, and it was kinda magical. It’s one of the joys of filmmaking and hopefully one of the joys of watching a film like this: to go back in time.”

Nielsen concurs. “For me, one of my treasured moments was when we were shooting early morning, the scene coming home from the opening party. And we’re sitting in our gorgeous, vintage car – and going up the main street of Baku, which hasn’t changed since then, and it’s now been covered in this yellow sandy earth – and the street’s been filled with horseman and all kinds of tribal people. It looked incredible. You did feel transported.”

Outside of Baku, the production also shot at the oil-fields, where Ali chases Malik after he kidnaps Nino. The ensuing fight, in which Ali kills Malik, takes place in a pond covered with a slick of oil. “It was below zero and really cold,” remembers Bakri, who went into the oily water without a wet-suit under his costume. “The pond was freezing. I almost died! My heart just stopped for a minute! Oh my God! I really thought I was going to die, when he first threw me into that pond. It was crazy.”

For the final scene, where Ali faces off with the Bolshevik army, the production travelled to Gadabay in the west of Azerbaijan. “That was a mind-blowing location,” says Wakefield, “about as close to the edge of the world as I’ve ever been.” Staging this dramatic scene, the crew rebuilt an ageing railway bridge, putting a track across it before blowing it up for the film’s spectacular and tragic finale. Yet it wasn’t the most taxing element of the eleven-week shoot.

Shooting in the Caucasus Mountains was particularly challenging, says Kapadia. “The reality is you just lose a lot of time. You have to be ready for the weather, for the changes. You just have to go with it. We did end up losing quite a bit – half the time we had scheduled we lost, because we had one real bad day of weather. The roads were not passable. It all comes down to time and how much you have. But it looks amazing; all that stuff is beautiful to look at.”

The production took to the wondrous ancient mountain village of Khinaliq to film the scenes where Ali heads to Daghestan after he kills Malik. “You’d sit there and wonder how they built it,” says Bakri. “It looks impossible! Then you’d learn its five thousand years old…but it gives you, as an actor, a lot, because that’s what Ali experiences. He goes up there and he’s stunned that there are people in this country that live like that. It changes something in him. The two years he spends in there, he becomes a man.”

For the cast and crew, it meant travelling up to location in off-road Lada Niva 4x4s. “Once you get up to the village, you can’t get anywhere else,” says Wakefield. “You’re completely cut off.” Valverde embraced the isolation. “It was cold but so beautiful at the same time,” she says. “For me, it was such a privilege to go to the mountains in Azerbaijan. It’s an experience that I’ll never forget. We realised how challenging the film was at this point, which made all the crew become really close.”

After eight weeks in Azerbaijan, the production then moved to Istanbul, Turkey, to finish the shoot across the final three weeks. With the city providing several interiors for scenes set in both Tehran and Tbilisi, it also proved a happy hunting ground for Clapton, who sourced both fabrics and costumes there, including a beautiful jacket she earmarked for Ali that she picked up for a song. “We were just leaving on the last day and I saw it and said, ‘Is that an Azeri costume?’ And it was.”

It all adds up to a spectacular-looking production shot in a country rarely seen on film. “In terms of locations, it will feel like a much bigger project,” says Thykier. “One of the reasons of coming here was that there was lots of stuff you haven’t seen before. Asif is a filmmaker who likes big, epic vistas and this should feel like a big, epic story. I didn’t need to do a lot of visual effects for that; I just needed to go up and shoot the landscapes. We did it the old-fashioned way.”

EPILOGUE...

How will contemporary audiences react to Ali and Nino, a century-old love story set in a country that, for many, is an exotic and faraway locale? Will they relate to these regal lovers? “In my opinion, any love story doesn’t have a concrete audience,” says Valverde. “I think nowadays there are still so many problems to be with someone that you love...so I think this film is going to be very modern.”

Indeed, Ali and Nino has numerous relations with our world – from squabbles over oil land to issues surrounding marriage between those from different religions. “It’s set a hundred years ago but everything in the story is somehow relevant,” says Kapadia. “That’s what I’m hoping to do with the film; to make it seem more relevant now. Even though it’s of a period, I felt: ‘I want you to forget the period when you’re watching it.’ It could be happening now somewhere.”

Nielsen, in particular, believes the message about relationships between those of different faiths is crucial. “God knows, we need stories of inter-marriage and the kind of attempts at neutral respect. I just think we can’t have enough of those stories. I really, really, truly believe that that’s an important thing to tell and it’s also more true. I believe that ultimately people on this planet are more ready to be accepting of each other than not.”

Bakri concurs, summing up the core theme in Ali and Nino as love. “It’s about the love of your life and your love for the country. What is love? It’s like this line between the love for your country and your love for your loved one. Is it the same? Maybe not. That’s what the movie asks.” Or as Patinkin so rightly states, in Ali and Nino, “It is love that is making the final decisions in every port.”