|

|

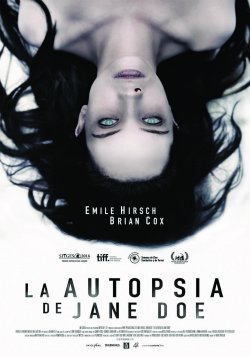

SINOPSIS

Un padre e hijo, ambos forenses, se enfrentan a la víctima de un homicidio sin causa aparente en su muerte. En el intento de identificar a la chica van descubriendo una serie de extraños y a la vez terribles secretos...

INTÉRPRETES

EMILE HIRSCH, BRIAN COX, OPHELIA LOVIBOND, MICHAEL McELHATTON, OLWEN CATHERINE KELLY, PARKER SAWYERS, JANE PERRY

MÁS INFORMACIÓN DE INTERÉS

![]() BSO

BSO

![]() CLIPS

CLIPS

![]() CÓMO SE HIZO

CÓMO SE HIZO

![]() VIDEO ENTREVISTAS

VIDEO ENTREVISTAS

![]() AUDIOS

AUDIOS

![]() PREMIERE

PREMIERE

GALERÍA DE FOTOS

GALERÍA DE FOTOS

https://cineymax.es/estrenos/fichas/111-l/102596-la-autopsia-de-jane-doe-2016#sigProId0c19712d70

INFORMACIÓN EXCLUSIVA

INFORMACIÓN EXCLUSIVA

THE ROOTS OF JANE DOE...

Like all good films should, THE AUTOPSY OF JANE DOE took shape over a curry. Writing partners Richard Naing and Ian Goldberg met with producer Eric Garcia in an Indian restaurant in Los Angeles. “They initially pitched me a couple of lines,” remembers Garcia. “Father-and-son coroners get a body in, they start to do the autopsy, secrets start to come out and weird things start to happen in the morgue.”

The concept had actually been brewing for some time. “I remember when the idea first came to us, it was such a raw kernel,” says Naing. “All we knew was that we wanted to do a movie that was in the opposite vein of the previous projects that we’d written. We wanted to stay in the horror space, do something that was genuinely scary, that wasn’t tongue-in-cheek horror-comedy – and we wanted it to be ultra-contained.”

Particularly inspired by Roman Polanski’s claustrophobic films Knife In The Water and Repulsion, Naing and Goldberg began to flesh out the idea, developing the story of veteran coroner Tommy Tilden and his son Austin. Locating it in Virginia, though with the majority of the scenes inside the Tilden family morgue, the story proper begins when both men take delivery of an unidentified female corpse – named simply Jane Doe.

Sold on the idea, Garcia brought fellow producer Fred Berger on board. Berger was immediately excited by the unusual notion of setting a horror movie in a morgue. “It wasn’t a haunted house and there wasn’t an exorcism,” he notes. “The autopsy aspect specifically provided an incredible way into a mystery. We always compare it to Sherlock Holmes. The body is the set of clues and they’re the detectives.”

As Tommy and Austin figure out more and more about what happened to Jane Doe, and stranger events unfold, the writers decided it was vital to ground the autopsy in reality. “There is a logical, scientific investigation that’s going on – even while strange supernatural things are happening,” says Goldberg. “That’s really the source of the horror,” adds Naing. “Despite everything being grounded, there’s this other stuff going on that you can’t explain.”

It meant spending time researching autopsies. Naing and Goldberg met with Craig Harvey, chief coroner at the L.A. County Morgue, who gave them the guided tour. “There were a lot of details that came out of going to the morgue that ended up in the script,” says Goldberg. “Like the convex mirrors in the hallways or the bug-zappers there to catch the flies that come out of the bodies…that was something we saw there.”

Practical details weren’t the only benefit of visiting the morgue; meeting Harvey allowed the writers to discover just what it takes to work in this morbid business. “It’s this mix of seriousness but also humour and respect for the dead,” says Naing. “It was something we gleaned from reading about coroners, and from reading books that coroners had written, but then when you see it in action – in person, when you’re talking to Craig Harvey – then it fully clicked in.”

While the script was evolving over time, Garcia and Berger began setting up production. Early on, they partnered up with UK-based production and management outfit 42, led by Ben Pugh and Rory Aitken. “Fred and Eric had developed the script and gave me the script in the States,” recalls Pugh. “I said to them, ‘Although it’s an American film, you should do this in the UK. We can do it in the particular way, at an appropriate budget level, and cast great actors.’ And they were interested in that.”

With 42 on board, helping to raise financing and jump-start the casting process, it meant that the production swung towards a London shoot – something that fitted with Garcia and Berger’s ideas for the script. “We wanted to bring a European feel to it,” says Garcia. “To us, we knew it was different and special as a horror film, and we wanted to find a way to do it a little bit differently. We wanted to bring a certain European element – that didn’t feel like a traditional American horror film.”

A key decision, of course, was who to bring in as director. Topping the list was Norwegian filmmaker André Øvredal, who gained critical plaudits for his 2010 film Trollhunter. When he read the script, he was immediately gripped by a story far removed from the found-footage style of Trollhunter. “I read it in forty-five minutes,” he says, “which is easily the quickest I’ve ever read a screenplay.”

Representing the perfect opportunity to make his English-language debut with, he was particularly taken with the script’s central relationship. “It is father-son story,” he says, “about unresolved issues between them that finally come to the surface, in a really intense situation, where they’re pushed to really handle what they haven’t handled between them before. Definitely, that’s the core of the film.”

Øvredal’s appreciation of the script left Garcia impressed. “He understood it in a way where he wasn’t just fawning over it. He loved it but he also said, ‘These are the things we need to focus on.’ He had a vision for it that we felt amped up what ours was. To me, it seemed like a great way in for him – where he could take something which had so much potential and bring something to it.”

CASTING AND CHARACTERS...

Finding the right actors was always going to be crucial for THE AUTOPSY OF JANE DOE – particularly given so much of it is a two-hander. “We knew we needed two heavyweights,” says Berger, and that wish was duly fulfilled with the casting of veteran star Brian Cox (Manhunter) as Tommy Tilden and Emile Hirsch (Into The Wild) as his son Austin. “In our wildest dreams, this is the best cast we could possibly have,” adds Goldberg. “We kept waiting for them to say it was a joke.”

A joke it wasn’t. Both Cox and Hirsch were hugely excited to take on the project. “It’s a great script,” says Cox. “I thought the guys who wrote it had done an amazing job. I was very impressed by the vision and daring of the piece. You just had to hand it to them. And then with André…he’s an amazing director, like a modern Hitchcock. He keeps it all in his head. He doesn’t storyboard, but he knows the shots intimately. And if it’s not right, he will sort it out until he gets it right.”

Cox immediately got a handle on Tommy – a professional long since deadened to the horrors of his job. “It kind of scares him in a way; the fact he’s a little inured to what’s going on. That’s what’s so interesting about it.” When strange events begin to happen as the autopsy on Jane Doe occurs, “everything is called into question”, says Cox. “He’s left very adrift as all of his belief systems have been completely undermined.”

The pairing of Cox with Emile Hirsch felt perfect, says Berger. “We were almost worried when we got Brian, because he’s such a good actor, and such a strong, experienced presence, that it’s not as easy to find guys in their late twenties, early thirties, who have that same calibre of experience and gravitas, and can go toe-to-toe with someone like Brian. But Emile and Brian, they immediately had this great dynamic that mirrored the characters: a paternal, playful rivalry.”

Øvredal couldn’t have been happier. “I really learnt so much from working with Brian, first of all. I was floored by his natural instinct when it comes to how a scene can be played...and he added so much depth and sense of reality to Tommy’s character.” Likewise his younger co-star, Hirsch, proved ideal. “His range is enormous! He has such a fine instinct for what is true to the character in a moment.”

Hirsch was particularly keen on researching the world of autopsies – and visited the L.A. County morgue on his 30th birthday. “It’s the biggest under-one-roof coroner’s office, I think, in the world,” he says. “So I went from never having seen a dead body, ever, to seeing 500 in one day! For someone who has never seen something like that, it’s really traumatising, mind-blowing, soul-searching and gut-wrenching.”

It was also invaluable. “By the time I got to the set, I knew what the real thing was like. I’d seen all these autopsies – people getting their skulls sawed open, their brains coming out, and their chests carved up. I was watching all this stuff, with my friggin’ jaw on the floor!” He smiles. “You take that elevator down to the basement and the doors open and all of a sudden there are bodies everywhere, and you’re just like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m so happy to be alive!’”

Cox, on the other hand, had no desire to see a real-life autopsy. “I couldn’t handle that. That was too much for me! I watched a video – a drug overdose. I just saw them cut down into her guts, and I thought, ‘Oh God! It is so debasing.’” Hirsch laughs at the memory. “I showed Brian a video of a real autopsy. I think it scarred him for life!” He was, though, hugely grateful to collaborate with his co-star. “He’s one of these old oaks that you’re lucky that you get to work with; especially as I had him all to myself.”

The other key role to cast was that of Austin’s girlfriend, Emma. British actress Ophelia Lovibond was one of the first through the door. “André and I had the same reaction – that we’d be lucky to have her,” recalls Berger. “We kept meeting other people and André kept saying, ‘Why are we even seeing other people? No-one is coming close.’ We also just hit it off with her as a person. She’s really sweet, lovely and hard-working. Also, that name – who forgets that?”

Lovibond, who recently starred in Marvel’s hit film Guardians of the Galaxy, was immediately taken with Naing and Goldberg’s script. “When I was reading it, it was really creepy. It felt within the realms of hostility. It does it slowly but surely. It was creepy...and those environments are inherently spooky, even if you don’t believe in ghosts. You are surrounded by cadavers – it’s a bizarre world. So it’s a good setting for a horror film.”

In her case, Emma is something of the motivating force – the girl who wants to take Austin away from his family’s grim business. “You need to see that he’s got a life outside of this, and that’s why he wants to leave. He doesn’t just want to be like his Dad, and be in the same job in the same town for the rest of his life. And I’m very much the catalyst for that. I’m trying to galvanise him to do something for himself. I represent this other life that is available to him.”

Hirsch, meanwhile, sees his character as conflicted – wanting to take care of his father while also debating whether he should move on. “He’s 30 years-old. He’s a grown-up. And he’s trying to navigate his own life and make decisions, but I think he’s made more peace with his father than some other coming-of-age movies, where it’s like…‘I gotta get out of town, Dad!’ It wasn’t quite as adolescent as some of those versions of that dynamic are.”

BRINGING JANE DOE ALIVE...

If there’s a real unsung hero of THE AUTOPSY OF JANE DOE, then it is actress Olwen Kelly – cast as Jane Doe herself. “Playing Jane Doe was more challenging than I had initially anticipated,” she remarks. “How hard can one imagine lying around to be?” Of course, as she soon found out, the role required a great deal more than simply that: patience, endurance and stillness were the order of the day.

To begin with, Kelly had to endure an entire cast being taken of her body – first her head, then her torso and legs. This was pretty terrifying as I can’t bear to have my head under water so for it to be submerged in clay and to have all my senses taken away from me was quite a challenge – but if you stop halfway through, you’ve got to go right back to the beginning and start again. Fortunately, we got through it in one go.”

Another part of her preparation was attending yoga meditation classes – the ideal way to practice how to be as still as possible. “I usually attend a faster flow yoga class so I did find it very difficult to be so still at first but I ended up really enjoying it,” Kelly notes. “I practised shallow breathing a little prior to filming as I’d been told that this was the trick to playing dead but more often than not, the prosthetics and/or my body position dictated how I had to breathe.”

Even so, nothing can quite prepare you for playing a naked corpse on set in front of other actors and crew-members – with your body subjected to lying on a cold marble slab for long periods. “She’s the real hero. She’s the real badass,” nods Hirsch. “It’s so hard to do that, to hold your breath like that, and that slab can get super-cold and uncomfortable…especially when you have these people poking and prodding you and lifting up your arms and legs.”

On top of that, Kelly had to contend with wearing various prosthetics as Jane Doe’s corpse is gradually opened up during the course of the autopsy. “The prosthetics were so creepy at first that I couldn’t look at myself in a mirror sliced open or dripping with blood,” she says. “But by the end I had pretty much forgotten that I even had them on. I’d only remember if I was chatting to someone off set and they had a vague look of disgust or morbid fascination on their faces.”

Much of her free time was spent washing dirt, fake blood and “god knows what else” out from her hair and underneath her fingernails. “But I suppose I didn’t have to wax or shave my armpits for the duration of filming so that was a time saver,” she laughs. She also had to endure the wit of various cast and crew members. “There were plenty of jokes about how I was looking a little pale, peaky or unwell, in the corridors or at lunch, as I’d be in full make-up.”

Cox admits it was eerie, having a disrobed, prosthetics-clad Kelly on set. “At first, as she’s naked, it’s quite startling. But after a while you just got used to her. You just got used to the fact she was this cadaver.” The actor was left hugely impressed by her work. “You couldn’t tell that she was breathing. She was remarkable. She wasn’t some kind of extra cadaver who was lying there. She was really focusing and contributing an enormous amount.”

Working closely with Kelly to transform her into Jane Doe were make-up and hair designers Bella Cruickshank and Jemma Harwood and prosthetics make-up designer Kristyan Mallet. Designing the Jane Doe prosthetics was particularly challenging. “Everything we made had to function,” says Mallett. “We made a Jane Doe dummy that had to be built in layers from the outside inwards. This would then be cut open and stripped back showing skin, fat, bones and organs: layer by layer like an onion.”

Berger admits that they were unsure how the dummy would look; with the construction of it a delicate and tricky procedure, it meant the team didn’t see the finished version until a week before the shoot. “You’d be amazed at what goes into creating these organs and dummies – it’s so meticulous,” says Berger. “It was just so much more detail on a daily basis that you’d think about. Each strand of hair has to be tucked in, individually. Each organ has to be coated with blood.”

While prosthetics are a regular part of the modern filmmaking process, THE AUTOPSY OF JANE DOE presented a unique problem for Mallett, with his work under an unusual amount of scrutiny under the camera. “Everything had to be as perfect and as real as we could possibly manage. André very much wanted it to be a journey following the autopsy closely, looking and listing the clues as the story unfolds. He also didn’t want it to be gory – or grotesque – but very real and have Jane Doe always looking very serene.”

Vastly experienced – not least on BBC medical drama Holby City – Mallatt had already been a spectator at various live surgery procedures in the past in researching other projects. He was also able to draw from photographic images from forensic pathology reports and a number of graphically illustrated medical books already in his library that were “essential to making all the items and prosthetics for this film”.

Similarly, the film’s make-up team had an extensive library of images collected over the years. “We did lots of research on dead bodies,” says Harwood, “all of the different ways a body can decompose, all the patterns and colours that form.” As with the prosthetics, Øvredal’s criteria was clear: “He really knew what he wanted with Jane, which was for her to look perfect but real, dead but not decayed,” adds Harwood. “Jane could not look like she was wearing any make-up at all.”

Even with both departments working harmoniously, visual effects were also used. “There were a million little details,” says Berger. “It’s a real body – we can’t just punch out her tooth or cut her tongue out!” One of trickiest shots involved real flies being applied to Jane Doe – which meant freezing the insects for fifteen minutes before unthawing them. “We were just waiting for the flies to wake up – just blowing and blowing,” laughs Berger. No flies, it should be added, were harmed in the making of this movie.

DESINGNING AND SHOOTING JANE DOE...

When it came to shooting THE AUTOPSY OF JANE DOE, Øvredal knew exactly what he wanted. Matching the very authentic feel the script contained, “My main reference was to go for a style that would resemble movies like Se7en, which was a thriller, which is a very, very grounded thriller. And to counter the potential of the audience catching up with us too soon, to really stick to that grounded sense of reality that you find in movies like that.”

With a story set almost entirely in one location, it allowed for a very unique opportunity. Rather than find a working morgue to shoot in, the production hired a 22,000 square foot warehouse space in Bromley-By-Bow in East London and turned it into a sound stage. It meant the entire interior of Tommy and Austin’s morgue could be built – complete with interconnected corridors, storage rooms and, of course, the autopsy chamber itself.

In charge of the set was production designer Matt Gant. “There was so much unusual action and SFX to take into consideration on this film, shooting on location would have been very difficult,” he says. “With a studio set we are able to remove ceilings, cut camera traps in walls if required and also benefit from the convenience of being on a stage and having the working space for the crew outside of the sets. Shooting on location would not have been impossible, but would have been more time consuming and difficult.”

With just four weeks to build the set, Øvredal’s guidance was crucial. “André was very keen that the film didn’t start off looking like a typical ‘genre’ film. He wanted the morgue to feel homely, comfortable, colourful and bright. The guys are very comfortable working there – a place that their family has worked in for years. There was to be nothing obviously gothic or sinister about it. We thought that if it felt every day, when things start to turn for the worse, the audience will feel a greater sense of discord and unease.”

When it came to the autopsy room, Gant was fortunate in that he’d already visited several in the past. “I had a pretty good understanding of the layout and the practical and technical concerns of the space,” he says, though in addition, he bolstered his knowledge by attending several working mortuaries and also consulting various pictures from the L.A. County morgue – useful for determining the differences to the British-built versions he’d seen.

“The design started with the cutting table, or slab, which I wanted to look like an altar and to be the centrepiece of the set,” he adds. “I’d imagined that is was probably one of the oldest parts of the family morgue and so had been used by successive generations of Tilden men.” Dismissing the alternatives – white porcelain (terrible for lighting) or stainless steel (too modern-looking) – Gant designed the slab in green marble, “in an art deco style, as if it dated back to the 1920s.”

The overall effect created by Gant left both cast and crew impressed. “Matt did such an amazing job,” says Garcia. So much so, the night before the shoot began, he was on his own on the set, taping some video footage to send to his wife back in the States. “I got halfway through – and I thought, ‘I need to stop. I’m terrified!’ I knew full-well. I’ve been there when it was nothing. I watched it when it was tape on the floor, and I watched the walls go up. But once I was in that space, I was really scared!”

For the actors, working on a fully-realised set, one that felt like a working morgue, was incredibly helpful. “The location is much a star of the film as anything else,” says Cox. “Those rooms and the production design – and the fact that we’re locked in that area and we can’t get out of it, it had quite an extraordinary effect on the way the whole shoot moved and the detail of the various autopsy elements.”

In particular, with unlimited access to the film’s central location, Øvredal was able to do what few films ever manage – and shoot scenes in order. “I have to admit,” says the director, “I don’t think the movie could’ve been made without shooting it chronologically. Being able to do that was absolutely crucial. There were so many instances, throughout the production, where that was very fruitful for everybody.”

With the morgue getting increasingly trashed as the story unfolds, shooting chronologically eased the pressure on the design team. Likewise, as the autopsy took place, and the Jane Doe corpse was gradually dismembered, the prosthetics could be peeled back in layers. The alternative – going back and forth, repairing areas of the corpse that had been destroyed for scenes shot later in the story – “would have made this project impossible for the budget it was made”, notes Mallett.

Yet, it was also useful for the actors to grow their relationship between each other.

“We were constantly building, and then going to the next scene, and then going to the next scene,” recalls Hirsch. “We were able to find these beats and moments very naturally and very easily. We didn’t have to guess levels of hysteria out of sequence.”

Lovibond concurs. “It is such a rarity to shoot chronologically,” she says. “You could pitch your performance, so you were much more informed. I did really enjoy it.”

The actors also rarely left the set, with Hirsch and Cox adopting Tommy’s office as their own chill-out area between takes. “There were a couple of sofas there and that ended up being a kind of a green room for them, which was a very, very nice way to get comfortable in each other’s space,” says Øvredal. “We needed that,” admits Cox. “We needed our space. It was either that or returning to one’s dressing room.”

While the actors were relaxing between takes, Øvredal still had to stay alert: designing each set-up was all important. “Repetition is your main enemy in shooting in one location,” he notes. “You will end up starting to repeat yourself, one way or another. But the good part is the script has a lot of variation. We realised in the edit that we have to cut scenes with a different temperature than a previous scene in the same location.”

One of the most complex sequences was shooting the fire that spreads through the mortuary late on. “In the real world,” explains special effects supervisor Scott McIntyre, “flames tend to behave in a consistent manner – mainly rising vertically and settling at a specific height depending on the quantity of flammable fuel used. But here there was a desire to have the flames spread in a slightly unnatural, organic way…so specific things would get burned and others escape damage.”

Using trails of cool-burning solvents and alcohols, McIntyre and his team were able to control the fire and create “what looks like a web of flame all around the room”. He also pays tribute to the “exceptionally helpful” make-up team for these sequences – matching the fire-resistant Jane Doe dummy with the lifelike version, touching it up where required, “without which a more obvious switch would be seen and become a headache for the VFX wizards in post-production to deal with”.

For Øvredal, it was a huge learning curve. “All the special effects that were in this movie, like the physical effects, were mostly new to me, but I’ve done a lot of commercials and you do a lot of practical stuff there as well. Sometimes, there were big surprises when you’re shooting with an actress, and you had to change over to the dummy in the middle of the scene, then go back to the actress later in the scene again, because you need an extreme close-up of her skin that any dummy just can’t do.”

Despite the film largely set around the morgue, two exteriors were also required. The outside of the morgue was shot at a house in Kent that boasted the perfect American-style design. “It would be hard to find it in the States, let alone England,” remarks Berger. “It had a white-picket fence and American post-box. It looked incredibly old but it was built four years ago with refurbished materials. It had a gothic horror vibe to it – and that was perfect.”

The other exterior was for the scene set at the Douglas house that opens the film – when Sheriff Burke and his men discover Jane Doe’s corpse buried in the basement. Locations manager James Player discovered a cul-de-sac in Esher in Surrey that felt remarkably American. “It was one thing to find one American house, but the entire neighbourhood looked like it could be Long Island or Florida,” says Berger. “It was really bizarre how perfect it was.”

Along with the rest of the team, the results left Cox impressed by what he saw. “André understands the psychological scariness and nastiness of the script. He really has a grasp of that. But it’s always true. There’s never the bogeyman; it’s never that. It’s based in a horrific logic.” He was left in no doubt about the effect THE AUTOPSY OF JANE DOE will have on audiences. “I’ve got a feeling it’s going to be quite scary,” he says. “It scared me!”